The professor in me is always curious to discover what a class finds most memorable -- what nuggets will they carry with them long after our course together ends? By way of review, I surveyed my OLLI class at Aquinas College during the last meeting (May 19, 2011), asking them what they most enjoyed learning in "The Amazing American Revolution." More than 50 students participated in polishing these nuggets.

10. Don't believe everything you hear on cable TV. Most commentators don't know the founding well at all. To get a better grasp of what Gordon Wood calls "the most important event in American history, bar none," it's useful to correct some misconceptions.

|

| Misinformation began early in the republic's history. This painting is typical in that it depicts the founders as unified statesmen possessing calm resolve. Yet at the conclusion of the Constitutional Convention, 16 delegates would not even sign the document they had debated. This 1856 painting by Junius Brutus Stearns -- titled "Washington as a Statesman" -- shows the General addressing the Constitutional Convention. It is at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond. By the way, Washington spoke only once at the Convention, toward the end of the deliberations. |

- Despite assertions to the contrary by some cable TV commentators and pols, the founders were a diverse lot when it came to religion, philosophy, and politics. That's why the question -- What would the founders do? -- is tricky. True, they shared the conviction that King George III and Lord North had violated the English constitution to an unconscionable degree. Applying the principles of the 1688 Glorious Revolution, they agreed to throw off the British Crown (though some were willing to crown George Washington in his stead). They also subscribed to the idea of "ordered liberty" more than we do. Beyond that, the founders could not even agree on what the American republic should look like. 16 of the delegates to the Constitutional convention refused to sign the document. Splitting up into Federalists and Antifederalists, most of the former championed a commercial republic (Hamilton); many of the latter, an agrarian republic (Jefferson).... You could hardly find two more diverse leaders than John Dickinson and Sam Adams. The intellectual antipathy between John Adams and Tom Paine was palpable.... Perhaps it was precisely the tensions among them that led the founders to become the greatest generation of statesmen ever.

|

| The most famous duel in American history: Aaron Burr, our sitting vice president, killed Alexander Hamilton, our first treasury secretary, in Weehawken, NJ, on July 11, 1804. |

- It is mistaken to think that the founders basically got along well with one another. Some wore white hats; some wore black hats. Like the rest of us, they nursed resentments, held grudges, and had knock-down-drag-outs. Recall: a sitting vice president shot and killed the first secretary of the treasury in a duel. George and Martha Washington felt personally betrayed by Jefferson.... Then there's John Adams, who had a plethora of apparent foibles. He could not stand Thomas Paine. He poked fun of John Dickinson for hiding behind the skirts of his Quaker wife and mother-in-law. He envied the credit George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and Thomas Jefferson received for the founding. By the Election of 1800, Adams and Jefferson were not even on speaking terms. Each of these "statesmen" had mobilized partisan newspapers to write such scurrilous things about the other that it is a miracle they ever restored their friendship. The campaign rhetoric in 1800 was much more vicious than anything you see today, even on cable TV.

|

| Ever wonder how Gouverneur Morris lost his left leg? |

- It is also mistaken to think that all the founders were buckled-shoe Puritans in their private lives. Several of our statesmen were not "family values" people at all. Luther Martin was such a lush that historians like Gordon Lloyd joke that it would be more accurate to call him "Luther Martini." Gouverneur Morris's many affairs on both sides of the Atlantic -- including sharing Talleyrand's mistress -- gives new meaning to the idea of (to use his words in the Preamble) "domestic tranquility." While Treasury secretary, Alexander Hamilton had a notorious affair with the financially desperate Maria Reynolds, making him vulnerable to bribery. (As Hamilton himself later confessed, "I took the bill out of my pocket and gave it to her. Some conversation ensued from which it was quickly apparent that other than pecuniary consolation would be acceptable").... In his Autobiography Benjamin Franklin admitted he frequently visited prostitutes; moreover, he was not very considerate of his wife Deborah, abandoning her for long periods of time; and he refused to reconcile with his son when he declared with the Tories. George Washington was still flirting with Sally Fairfax after his engagement to Martha. Washington's famous will, in which he released his slaves (the only founder to do so), certainly betrays mixed motives upon closer inspection. Thomas Jefferson was not only accused of sleeping with his teenage slave, Sally Hemings, but also with trying to seduce his neighbor's wife, Betsy Walker. The sins and peccadillos of our founders would fill an Everest of People magazines.... But that's okay. It is important to see the founders as they were. They were not marble statues, cold and unapproachable and inaccessible. When we bring them down from Mt. Olympus, when we see them as they were, warts and all, we can respect them all the more as flawed humans who nevertheless accomplished much good.... Plus, we can identify with them. If these flawed human beings were capable of such heroic personal sacrifice in the service of a greater good, then perhaps we really can follow in their footsteps and expect better from ourselves.

|

| Politically, America was founded as a constitutional republic. But direct democracy was practiced in early New England town meetings. This illustration is from a civil government text used in the early 20th century. |

- It is misleading to assert that America was founded as a democracy. That statement is only partially true. Constitutionally, America was founded as a republic. The populist element in our early history was situational. Ad hoc direct democracy arose on the Mayflower, in New England town meetings, and along the frontier. Moreover, our civil society, marketplace, and militias were democratically organized. The democratic principle in our culture would spill inexorably over into politics during the Progressive Era a hundred years after the founding. But the national government would not change significantly until many decades after the founding generation had passed. Strictly speaking, the national frame of government that came out of Philadelphia in 1787 was republican. A republican constitution by definition balances rule by the one (presidency), with rule by the few (Senate and Supreme Court), with rule by the many (House). America was founded as a constitutional republic.

- I sometimes hear it said, erroneously, that America was the world's first republic. Actually there were numerous republics that preceded America. Ancient Carthage was a prominent republic that contended with Rome for control of the Mediterranean. Ancient Rome was a republic for almost 500 years. Medieval Venice was a republic for more than 1,000 years. Prior to the American Revolution, in the 17th century, the Dutch formed a powerful commercial republic, and Britain experimented with republicanism under Cromwell. It is more accurate to say that we were the modern world's first constitutional republic.

|

| Charles Carroll of Carrollton (Maryland) was the only Catholic signer of the Declaration of Independence and the last surviving signer of the document. He was educated in Europe by the Jesuits. This serene oil painting, by Thomas Sully in 1834, fails to convey all the suffering Carroll and his family endured both as Catholics and as nation founders. Bradley Birzer's authoritative biography, American Cicero, brings to life one of the most fascinating statesman of the founding era. |

- "America is a Protestant nation" -- a largely true statement at the time of the founding, but one that needs qualifying. Most citizens were indeed Protestant, but two percent of the population was Catholic and heterodox faiths abounded, as did people who professed no faith at all. In British North America there were numerous Quaker settlements, for example, and many of our foremost founders were either Unitarian (John Adams) or Deists (Jefferson, Franklin, Paine). Only once in his public life did George Washington speak the name of Jesus. (He was nominally Anglican.) Only one of the nine most prominent founders, John Jay, was a devout, orthodox, church-going Protestant during the revolutionary period. During one particularly tense session at the Constitutional Convention, Benjamin Franklin suggested that the delegates pray, to which Alexander Hamilton quipped that Americans had no need of foreign intervention. There is no question that most American settlers were Protestant, and that most of the founders were Protestant. But it is also accurate to say that a small number of prominent founders were like flying buttresses -- supportive of the church but happy outside of it.

|

| Texas vaqueros helped win the American Revolution. This historical plaque in New Orleans commemorates the role of Spanish Governor Bernardo de Galvez in defeating the British. Galvez fed Spanish and American armies with cattle from Franciscan ranches around San Antonio, in the Spanish province of Texas. |

- When speaking of the War for Independence, it is misleading to concentrate solely on the upper East Coast between, say, Fort Ticonderoga and Yorktown. To do so is to neglect other critically important theaters in the Western Hemisphere. Historically, Boston and New York publishing houses tended to focus on their own region to the neglect of (1) the Carolinas, which saw some of the heaviest fighting in the war; (2) the Caribbean, where the French navy kept most of the Royal navy pinned down; (3) the West, where George Rogers Clark subdued Britain's Indian allies, even in far-off places around Fort Detroit; (4) the Southwest, where Spanish Governor Bernardo de Galvez kept the Gulf Coast and Mississippi River cleared of the British, with even Spanish vaqueros in Texas playing a logistical role. Each theater contributed to the successful quest of the Americans who sought independence. It's not just an East Coast thing.

Also:

- July 4th, 1776, is not technically Independence Day. As John Adams pointed out, July 2nd was the day when the Second Continental Congress voted on Richard Henry Lee's resolution (introduced on June 7, 1776) to separate from Great Britain. July 4th was the day the Congress voted to adopt the Declaration of Independence, setting forth the rationale for the break with Britain. It was intended for both for domestic and international consumption.

- George Washington was a great man, but he was not a great battlefield general -- certainly no Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, or Napoleon Bonaparte. In fact, GW lost more battles than he won. His strength lay in his ability to hold a ragtag army together, his example of sacrifice, his intelligence gathering, his holding an international alliance together, and his ability to walk away from power. That is why he was great and it is why we honor him. (Even his enemy, King George III, remarked that Washington's ability to walk away from power made him "the greatest man in the world.")

|

| A set of George Washington's dentures, obviously not made of wood. |

- George Washington did not have wooden teeth. His dentures were made of slave teeth set in ivory that were stained by tea, so they eventually looked like wood. They caused him much difficulty (stories about which prompts laughter at the expense of the Father of our Country).

- It is not true that democracies (and, by extension, representative democracies) do not go to war against one another. The German philosopher Immanuel Kant foreshadowed the "democratic peace theory" in his essay, "Perpetual Peace" (1795). Kant reasoned that a majority of the people would never vote to go to war, unless in self-defense. Therefore, if all nations were constitutional republics, international warfare would end, because there would be no aggressors. It's a bad theory refuted by history. Numerous times a body of people or their representatives have elected to go to war against each other: Athens vs. Sparta; Rome vs. Carthage; Great Britain vs. the U.S. in the War of 1812; the North vs. the South in the Civil War, and both, by the way, were the largest two democracies in the world at the time.

9. The American War for Independence was both a civil war and a world war. It began as a civil war. A formerly united empire consisting of Englishmen loyal to the Crown split up when about 1/3rd of the colonists in British North America decided they had put up with too many abuses for too long. They justified their violent breakout in the Declaration of Independence, citing some two-dozen specific abuses.... Within three years the conflict morphed into a world war, and here the larger global context is important. England and France had fought four wars in the hundred years leading up to the American Revolution. They had scrapped in Europe, the Indian Ocean, the Caribbean, and North America.... In 1754 a young George Washington precipitated the fourth of these wars in a glen in southwestern Pennsylvania. Britain eventually won the Seven Years War, but at a high price -- literally. The American Revolution grew out of the tensions that arose when Britain, financially strapped, taxed colonials without their consent to ease the crushing debt of empire. Patriot resistance led to the War for Independence, but Britain would end up fighting not just 13 of their former colonies, but also France, Spain, and Netherlands, all of which had scores to settle with the British.... After Saratoga, France came in on the American side hoping to humiliate the British after their own humiliation in the Seven Years War. Although France got the satisfaction of seeing Britain humiliated, her war debts, in turn, would lead to the calling of the Estates General and the outbreak of the French Revolution.... Out of the chaos of the 1790s rose Napoleon, whose wars in turn led to financial troubles that would open up the opportunity for Americans to purchase Louisiana, recently purchased by the French from Spain.... The American revolt is further linked to her former allies through the Haitian slaves who unsuccessfully attempted to break away from France and found the New World's second republic, and to all the South American republics that successfully broke away from Spain. It's all linked -- like that old toy, the barrel of monkeys. The American founding is better understood when seen in all its complex linkage to the broader world.

|

| The neoclassical painter, John Trumbull, actually took part in the scene above, titled "The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker Hill, June 17, 1775." The painting hangs at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. |

8. The casualty rate of the Revolutionary War was much higher than anyone today realizes -- second highest of all our wars. In the Civil War, America lost almost 2 percent of her population. In the Revolutionary War (which was also a civil war), America lost almost 1 percent of her population. Out of a population of 2.5 million, the Americans lost close to 25,000 people by mortal wounds, subsequent infections, and disease.... By contrast, in World War II and the War of 1812, the U.S. lost about 1/3rd of 1 percent of her population. In World War I we lost about 1/10th of 1 percent of our population. In Vietnam we lost an even lower percentage of our population.

|

| It was once common to depict George Washington sporting a Roman toga, symbolic of the old high Roman virtues -- labor, pietas, dignitas, gravitas, and fatum. This period piece from the 1840s, by Horatio Greenough, is part of the Smithsonian collection. |

7. The American founders were latter-day Roman republicans. Many could read Latin, were classically educated, and consciously identified with some of the leading republicans of ancient Rome. They especially valued the civic virtue of the ancient Romans that made men capable of great sacrifice for others and for the community.

|

| Cincinnatus put down his plow and took up his sword when he was called to lead Rome against tyrants. In this sculpture (in Cincinnati, OH), the republican leader is handing the fasces, symbol of constitutional authority in Rome, back to the republic's legitimate authorities. Fasces are a common symbol of republican power -- and also the origin of the word "fascist." Fasces are depicted in the U.S. House of Representatives on each side of the rostrum. |

- George Washington was alternately regarded as a Cincinnatus (for laying down his sword and returning to his plow) or Fabius the Delayer (for patiently avoiding a military catastrophe with the British). He also was a great fan of Joseph Addison's play, Cato, which he had performed again and again for his men. In both sculpture and painting, contemporaries frequently portrayed GW in a toga.

- John Adams, an attorney, looked back to the greatest lawyer of ancient times, the Roman republican Cicero, for inspiration.

- Alexander Hamilton signed his Federalist papers with the name of the early Roman republican, Publius. There is evidence that he signed early papers "Julius Caesar."

- James Madison signed his Federalist papers with the name of the early Roman republican, Publius.

- John Jay signed his Federalist papers with the name of the early Roman republican, Publius.

- In fact, when debating the merits of the Constitution, most of the Federalists and Antifederalists used Roman noms de plume.

- Nathan Hale's last words -- "I regret that I have but one life to lose for my country" -- were likely based on words from Joseph Addison's play, Cato.

|

| In this famous sculpture of George Washington by Houdon (in the Virginia Capitol in Richmond), the General and first President of the United States rests his left hand on the fasces, symbol of Roman republican power. Fasces were composed of a bundle of rods around an axe. Compare Washington's pose with that of Cincinnatus, above, who is handing the fasces (power) back to legitimate public authorities. |

- It was fashionable for earlier generations of Americans to have Roman names. Did you notice the painting of the Constitutional Convention of 1787 at the top of the page? The artist's name is Junius Brutus Stearns (1810-1885).

6. The American Revolution and founding should be chronologically and spatially s-t-r-e-t-c-h-e-d, seen as (1) beginning much earlier, (2) including more Indian battles in the West, and (3) ending much later than the conventional wisdom suggests. Following Longfellow's famous poem, we tend to put the start of the Revolution at April 19, 1775, when Lexington and Concord flared up. We conventionally mark the end of the Revolution at either the Battle of Yorktown in 1781 or the Peace of Paris in 1783. But John Adams claimed the American Revolution began much earlier, in a Boston courtroom in February 1761, when James Otis delivered a speech asserting that Americans had the right to interpret English constitutional principles and rights differently from British politicians back home. In fact, according to Adams, many Patriot Americans had already declared their independence from the mother country in their minds and hearts before a shot was fired.... But to mean anything, ideas on parchment had to be backed by victories on battlefields. Americans simply had to wear down the British will to keep them in the empire.... We tend to overlook the importance of the Indian battles. Successfully confronting Indian unrest among the Iroquois, Shawnee, Cherokee, and Miami was critical to the struggle for independence. Many Indian battles, even as late as Fallen Timbers (1794) and Tippecanoe (1811), were due to British agitation of her Indian allies who continued to harass American settlers in the West.... As for an ending date, Jefferson called the Election of 1800 the Second American Revolution. And the War of 1812 was widely perceived to be the Second War for Independence because it was not until the conclusion of that conflict that the British seemed truly resigned to having lost her 13 North American colonies.

|

| In 1794 the Battle of Fallen Timbers took place outside of present-day Toledo, OH. It should be seen in the context of the War for Independence and American Revolution. |

5. The American founders, a minority of the population, were gutsy. Given similar circumstances today, we would probably be either Loyalists or fence-sitters. I'd wager that most of us today would not be treasonous but play it safe. Americans in 1776 were, after all, part of the greatest empire on earth. We enjoyed more rights and liberties than any other people. Why risk it all?... John Adams observed that 1/3 of the population was Patriot, 1/3 was Loyalist, and 1/3 was opportunistic or neutral. We are not as animated by constitutional ideals and historic precedents as much as they were. Maybe some of us would tip our hat to the most conservative founder, John Dickinson. But probably not. The War for Independence was a vicious civil war here at home. Even non-combatants paid dearly. We'd seek convenience and try to avoid the pain.... American Patriots were fighting the superpower of the day, against the greatest army on earth and the greatest navy on the seas. The odds of winning were slim. There was much to lose if you committed high treason against the Crown, not least of which was life and limb. Most people are not willing to risk their all.... The American Revolution almost didn't happen. On several occasions, it was almost aborted. That's why I title my course, "The Amazing American Revolution." It is amazing that the founders pulled it off.

4. In its street plan, Washington, DC, is one of the great Baroque (and broke) cities of the world. Architecturally, it looks like a latter-day outpost of Rome. In plan, L'Enfant, Ellicott, and the McMillan Commission all reinforced the classical and baroque motifs. Even as late as the 1930s, FDR's Washington seemed to be competing to become the Third Rome (as were Hitler's Berlin, Mussolini's Rome, and to some extent even Stalin's Moscow).

3. George III was every bit the revolutionary that George Washington was. The king was a revolutionizing tyrant, destroying the English constitution and denying the ancient rights of Englishmen to colonial subjects. His tyranny was as revolutionary as George Washington's principled resistance was. Perhaps the American founding could best be described with the Burkean phrase, "a revolution not made, but prevented." For the revolutionary impulse was largely kept within bounds when compared to the later French Revolution or Russian Revolution. As the historian John Willson suggests, maybe this is the true achievement of the American founders, to form a more perfect union without turning the world upside down.

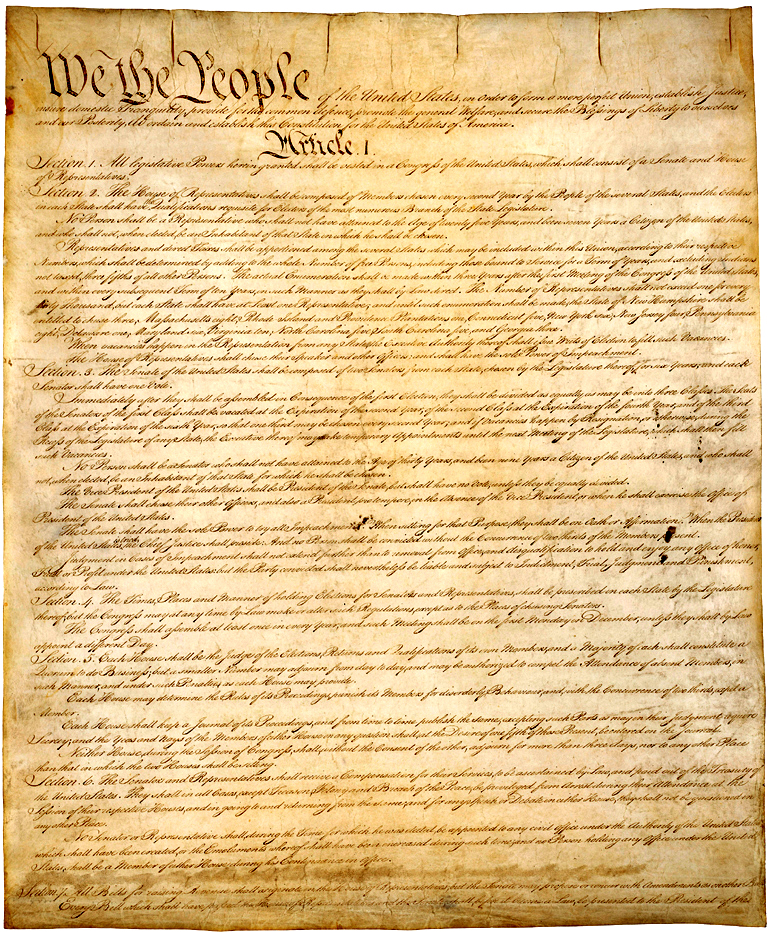

2. The founders' understanding of freedom was different from ours. They did not think it was the right to do whatever you wanted. They were not libertarians. The founders' understanding of freedom merged two intellectual streams of thought. One was the civic republican tradition, an inheritance of classical, Renaissance, and English Whig thought; it emphasized the citizens' duties to the commonwealth and engendered the habit of putting service before self. The other was the natural rights tradition, influenced by William of Occam, John Locke, and the Enlightenment; it emphasized the government's duty to the individual, especially to protect one's God-given right to life, liberty, property, and pursuit of happiness. Taken together, both the republican and liberal streams of thought recognize that freedom comprises rights

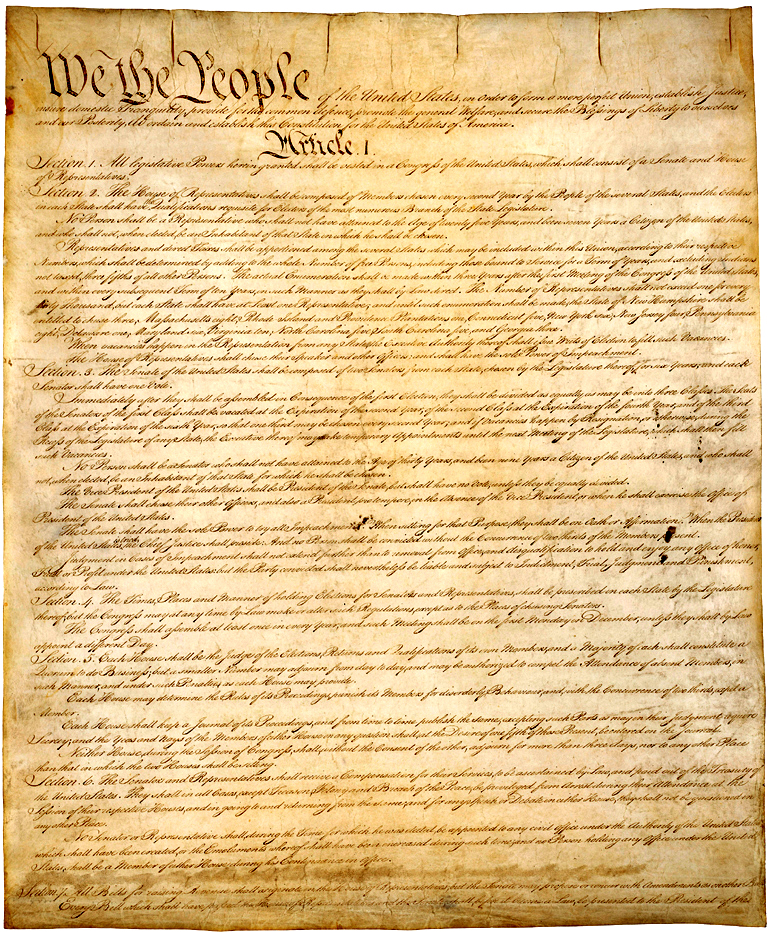

and duties.... Further, freedom must be ordered to be secured; otherwise it can devolve into licentiousness and/or anarchy, as Polybius, Sallust, Livy, and Tacitus taught when meditating on the Roman experience.... Gouverneur Morris's 52-word Preamble to the U.S. Constitution offers a sublime lesson in the five conditions that must obtain before a people can be truly free. Every American should know this wonderful little lesson in political philosophy.

|

| The first page of the U.S. Constitution containing Gouverneur Morris's 52-word Preamble, one of the most sublime lessons in political philosophy ever crafted. |

1. The founders spoke of our nation's happiness. They were concerned about posterity -- about our happiness. Of all the state papers ever produced, one of the most famous is the Declaration of Independence. And of all the phrases Jefferson ever penned, surely one of the most appealing to modern sensibilities is "the pursuit of happiness." That line has played a part in shaping the modern world. Yet most Americans today are not familiar with older conceptions of happiness. The founders would not have confused happiness with power, profit, prestige, pleasure, or pride in getting our way. What does the pursuit of happiness entail? To the founders, above all it meant reconciling the public duties of our civic republican tradition with the private rights of our natural law tradition. But the private sense of happiness does not end there. At the end of Sophocles' play,

Antigone, the chorus instructs us in the happiness we seek. The main ingredient of happiness is wisdom. How do we become wise? For most of us, punishment and suffering pound out our foolishness. They school us until we learn the lessons needed to live the good life. Experience teaches that wisdom mostly comes from keeping a clear conscience, worshiping God rightly, and learning from mistakes, our own and others'. If we are mindful of these things, we have a shot at being happy. We are smart about "the pursuit of happiness." For we know that, absent wisdom, there is no happiness.

* * *

Final thoughts in the final class

There were several honorable mentions cited by the class, nuggets that almost made it into the Top Ten. For example, they enjoyed learning about the critical moment in American history that occurred in Newburgh, New York, on the Ides of March 1783, when George Washington saved the new republic from impatient, angry officers who wanted him to lead a junta against the Confederated Congress.

One woman in class was fascinated by how rifling a gun barrel was a technological leap over smooth-bore muskets, increasing the lethal velocity of a lead ball. In a related vein, a man seized on Nathaniel Greene's brilliant strategy at Cowpens and Guildford Courthouse.

Of course, they enjoyed all the people stories -- of Nathan Hale's bravery in the face of death, of Molly Pitcher manning the cannon after her husband collapsed, of Abigail Adams watching the early battles with her children, of Ethan Allen and his Green Mountain Boys in the Grants, of John Paul Jones's daring-do off the coast of Scotland, etc. There is never enough time for all the interesting people stories, but they are what make history come alive in any class.

Bottom line: Time will tell, future historians will ratify, whether America is the greatest republic ever founded. A little perspective is in order. Our republic has existed less than 240 years. Chinese dynasties passed the baton for some 4,000 years. Egyptian civilization lasted some 3,000 years. The Venetian Republic lasted more than 1,000 years. The Roman republic lasted some 500 years. A fraction of that age, our American nation is a relative new-comer to the world stage. Are we up to the awesome task of continuing it? As Benjamin Franklin told the woman outside the Pennsylvania State House in 1787, the founders bequeathed to the American people a republic. Now it is up to us to keep it.

|

| The United States Capitol is freighted with architectural significance, marrying the eternal heavens with earthly ambition and achievement. Reminiscent of St. Peter's and (further back) the Roman Pantheon, the circular dome symbolizes the eternal first principles of a constitutional republic in which the people are sovereign under the rule of law. The rectangular floor plan that rises from the foundation symbolizes our nation's connection to bedrock, rich soil, and vast natural resources, a geographic grounding reinforced by the structure's orientation along the four cardinal directions. |

* * *

For more about the American founding, please see my other essays on this blog along with the many links to additional works.

For more about leadership, please visit the Hauenstein Center for Presidential Studies

http://www.allpresidents.org/.