|

| Garden of Eden, by Thomas Cole |

Humans have the primordial urge to return to Eden, so they try to see glimpses of Paradise everywhere they are. Beautiful landscapes are a vestibule of the Heaven that awaits them. They thus sanctify place and redeem time. The discipline of geography is a way of "finding" God, not in place, but through place. This primordial urge to return to Eden, to our original home, is very Jewish. To see unexpected beauty in a place -- for example, in a brilliant sunset -- is another source of happiness.

There is often the desire to strike out into the unknown, yet with the confidence that, if we follow the rules of the road, it will lead to a better place, one we've not been to before. Fixing our compass on a better place in the future is a very Christian aspiration. This hope in a better place in the future is another source of happiness.

There is often the desire to strike out into the unknown, yet with the confidence that, if we follow the rules of the road, it will lead to a better place, one we've not been to before. Fixing our compass on a better place in the future is a very Christian aspiration. This hope in a better place in the future is another source of happiness.

I. Journeying ... and the joy of geography

A great tradition of literature of travel, sojourneying, combines the joy of geography with the joy of words: Homer's Odyssey, Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, Dante's Divine Comedy, Steinbeck's Travels with Charlie, Pirsig's Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, William Least Heat Moon's Blue Highways)

Robert Pirsig in Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance (pp. 1-2):

"We are in an area of the Central Plains ... heading northwest from Minneapolis toward the Dakotas. This highway is an old concrete two-laner that hasn’t had much traffic since a four-laner went in parallel to it several years ago.... I’m happy to be riding back into this country. It is a kind of nowhere, famous for nothing at all and has an appeal because of just that.

Tensions disappear along old roads like this.... Chris and I are traveling to Montana with some friends riding up ahead, and maybe headed farther than that. Plans are deliberately

indefinite, more to travel than to arrive anywhere. We are just vacationing. Secondary roads are preferred. Paved county roads are the best, state highways are next. Freeways are the worst. We want to make good time, but for us now this is measured with emphasis on 'good' rather than 'time' and when you make that shift in emphasis the whole approach changes."

indefinite, more to travel than to arrive anywhere. We are just vacationing. Secondary roads are preferred. Paved county roads are the best, state highways are next. Freeways are the worst. We want to make good time, but for us now this is measured with emphasis on 'good' rather than 'time' and when you make that shift in emphasis the whole approach changes."

II. Geographical awareness heightens one's sense of irony, and irony can be a source of joy, producing a wry smile. Geographic irony includes:

|

| Mouth of a river emptying into the Indian Ocean in Mkambati Nature Reserve, Pondoland, South Africa |

1. The notion of the "mouth" of a river. It is a bad analogy to the human mouth because it gets it all backwards. We usually associate the mouth with the nourishment that is taken in. But the mouth of a river relentlessly discharges its watery nourishment from its "alimentary canal" -- its system of tributaries -- to an estuary that feeds land and marine life.

|

| The Father of Cool: Willis Haviland Carrier |

|

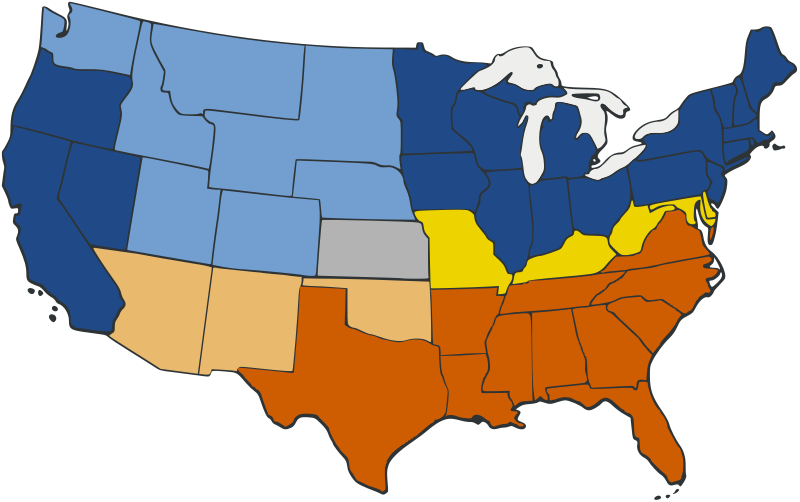

| The United States in the 1860s, during the Civil War |

|

| The joy of complexity: Illinois |

- Geologically, the state's foundation rocks vary from those of the Great Lakes Basin to those of the Gulf Coastal Plain.

- Geomorphologically, glaciated in the northeast, with moraines, but unglaciated in the northwest, in the driftless area.

- Ecologically, oak-hickory forests in the north, bald cypress in the south.

- These physical southern connections are reinforced by a host of other southern links. LaSalle unites the area to Louisiana in the contest for empire.

- The Mason-Dixon Line splits the state in two – the line is just five miles south of the state capitol building in Springfield.

- Illinois is regarded, properly, as a northern state. It was a free state that remained in the Union during the Civil War. After all, it is the “Land of Lincoln,” and Ulysses Grant called it home. Yet the southern third of the state has a southern feel and people speak with a southern accent because immigrants came in from Kentucky, across the Ohio River to the east.

- Illinois -- considered "western" in the early 1860s -- was important as a Civil War staging area at Fort Defiance.

- Chicago (big, new, modern) and Cahokia (relatively big, ancient, extinct) and places in between that cling to existence, places like Cairo (whose hopes have been dashed, but see the SIU proposal).